In this prelab, you will familiarize yourself with some of the design and implementation issues in the upcoming lab 3. Please write or type up your solutions, and hand in a paper copy before 10am on Monday. Remember, late prelabs receive zero credit! :-(

Overview

In this lab you will be writing a program that will read in a maze and then find possible paths from the start to the exit using different techniques.Part 1 - Representing the Maze

First let's talk about your basic maze. It has walls and pathways, and it has one (or more) starting point(s) and one (or more) exit point(s). (To keep things simple, let's just assume it has no more than one of each.) Furthermore, one wall is just like another, and any open space (not including start and finish) is also identical. So, we can think of a maze as being made up of individual squares, each square either empty, a wall, the start, or the exit.

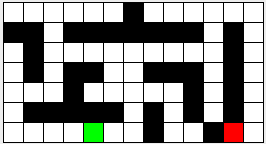

Below is a graphical representation of a maze. The green box represents the start, the red box the exit, and the black squares the walls.

We can represent such a maze with a text file of the following format. The first line of the file contains two integers. The first indicates the number of rows (R), the second, the number of columns (C).

The rest of the file will be R rows of C integers. The value of the integers will be as follows:

0 - an empty space

1 - a wall

2 - the start

3 - the exit

In terms of coordinates, consider the upper left corner to be position [0,0] and the lower right to be [R-1,C-1].

For example, this is the text version of the maze above (start is at [6,4] and exit at [6,11]).

7 13 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 1 0 0 1 3 0

The Square Class

-

Suppose you want to print out a representation of a Square class using the following substitutions:

Input Output Meaning 0_empty space 1#wall 2SStart 3EExit Write a toString method that returns the appropriate character (in this case, write actual code rather than pseudocode). Assume that the input is stored in a field called type. This is a perfect time to use a switch() statement [Weiss 1.5.8], although nested if-then-elses would also work.

The Maze Class

Once we have Squares, we should be able to set up the maze itself. Assume that the Squares are stored in a 2-dimensional array called maze similar to the following

Square[][] maze = new Square[numRows][numCols];

-

Write a toString() method that returns the maze in textual format. For the sake of my sanity, call your loop variables something like row and col.

For example, the maze above would be returned by toString as follows:

_ _ _ _ _ _ # _ _ _ _ _ _ # # _ # # # # # # # _ # _ _ # _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ # _ _ # _ # # _ _ # # # _ # _ _ _ _ # _ _ _ _ _ # _ # _ _ # # # # # _ # _ # _ # _ _ _ _ _ S _ _ # _ _ # E _Note that this is just one long string with embedded

'\n'characters to terminate lines.

Part 2 - Stacks and Queues

In this section of the lab you will implement your own stack and queue. For now, we'll just get some practice with them.

- (Weiss) Draw the contents of stack and queue data structures

for each step in the following sequence:

add(1),

add(2),

remove,

add(3),

add(4),

remove,

remove,

add(5).

Assume both structures

are initially empty.

Queue add(1) add(2) remove add(3) add(4) remove remove add(5)

Stack add(1) add(2) remove add(3) add(4) remove remove add(5)

Part 3 - Solving the Maze

Now that you have a maze, and you have stacks and queues, we can get down to business! The application portion of this lab will be to write a MazeSolver class (and associated classes), which will bundle up the functionality of determining whether a maze has a solution---that is, whether you can get from the start to the finish (without jumping over any walls). The algorithm one usually follows goes something like this: start at the start location and trace along all possible paths to (eventually) all reachable open squares. If at some point you run across the finish, it was reachable. If not, it wasn't.

Boiling this down into pseudocode, we have the following:

At the start

- Create an (empty) worklist (stack/queue) of locations to explore.

- Add the start location to it.

Each step thereafter

- Is the worklist empty? If so, the finish is unreachable; terminate the algorithm.

- Otherwise, grab the "next" location to explore from the worklist.

- Does the location correspond to the finish square? If so, the finish was reachable; terminate the algorithm and output the path you found.

- Otherwise, it is a reachable non-finish location that we haven't explored yet. So, explore it as follows:

- compute all the adjacent up, right, down, left locations that are inside the maze and aren't walls, and

- add them to the worklist for later exploration provided they have not previously been added to the worklist.

- Also, record the fact that you've explored this location so you won't ever have to explore it again. Note that a location is considered "explored" once its neighbours have been put on the worklist. The neighbours themselves are not "explored" until they are removed from the worklist and checked for their neighbours.

Note that this pseudocode is entirely agnostic as to what kind of worklist you use (namely, a stack or a queue). You'll need to pick one when you create the worklist, but subsequently everything should work abstractly in terms of the worklist operations.

- Run this algorithm on the example given at the top of this prelab,

where your worklist is a stack. Run it for the first 8 steps; show your

worklist after each step, as well as list (at each step) which squares

have been explored, and which have been marked (as in, which squares

have at one point in the algorithm been added to the worklist). To

make grading life easier, push adjacent squares onto the

stack in the clockwise order given, namely, up, right, down, then left.

Some of the entries are already filled in, so that you can tell if

you are on the right track.

The coordinates are in (row, col) order. Be careful to stick to that order

at the start after step 1 after step 2 after step 3 after step 4 after step 5 after step 6 after step 7 after step 8 worklist as a stack

(6,4)

(6,3)

(6,5)

(6,2)

(6,5)

(4,2)

(3,0)

(6,5)newly explored square N/A (6,4) (6,3) newly marked square(s) N/A (6,3)

(6,5)(6,2) (5,0)

- Now run the algorithm on the same example, where your worklist is a queue. Show the same work. Did things work differently? Do you think one worklist is better than the other (why, or why not?)?

worklist as a queue newly explored square newly marked square(s) at the start (6,4) N/A N/A after step 1 (6,5) (6,3) (6,4) (6,5) (6,3) after step 2 (6,3) (6,6) (6,5) (6,6) after step 3 after step 4 after step 5 (6,1) after step 6 after step 7 after step 8 (6,0) (3,6) (4,7) (4,5)

The MazeSolver Abstract Class

The next step in the lab will be to create an abstract class MazeSolver that implements the above algorithm, with a general worklist. Its abstract methods will be implemented differently depending on whether the worklist is a stack or a queue, but the main algorithm will remain the same. The MazeSolver class will have a private class member of type Maze, and the following methods:

- abstract void makeEmpty()

- create an empty worklist

- abstract boolean isEmpty()

- return true if the worklist is empty

- abstract void add(Square sq)

- add the given Square to the worklist

- abstract Square next()

- return the "next" item from the worklist

- Square step()

- perform one iteration of the algorithm above and return the Square that was just explored (and null if no such Square exists). Note that this is not an abstract method, that is, it must be implemented in the MazeSolver class by calling the abstract methods listed above.

In order to keep track of which squares have previously been added to the worklist, you will "mark" each square that you place in the worklist when you place it in the worklist. Then, before you add a square to the worklist, you should first check that it is not marked (and if it is, refrain from adding it).

The MazeSolverStack and MazeSolverQueue Classes

Now we will have to create two different implementations of the MazeSolver class---a MazeSolverStack and a MazeSolverQueue, both extending the MazeSolver class. These will not be abstract classes, and so you will have to implement the MazeSolver's abstract methods. Each class will contain as a class variable a worklist of the appropriate type (so, MazeSolverStack should have a class member of type MyStack<Square> and MazeSolverQueue should have one of type MyQueue<Square>). All you'll have to do to implement the abstract methods is perform the appropriate operations on the stack or queue class member.

- What are the benefits of having the MazeSolver as an abstract class?

Why not just make two different versions (one for the stack and one for

the queue). Are we really saving anything by using the single superclass

with two subclasses?

- Suppose the MazeSolverStack class' stack is called stack. What will the void add(Square sq) method look like? (Hint: it's really quite short.)

Tracing the path

In order to output the solution to the maze when you find the exit, you will need to keep track of the path that was followed in your algorithm. This seems to be a difficult proposition; however, there is a simple technique to solve the problem.

In order to keep from wandering in a circle, you should avoid exploring the same location twice. You only ever explore locations that are placed on your worklist, so you can guarantee that each location is explored at most once by making sure that each location goes on the worklist at most once. Imagine you were to "mark" a square by placing an arrow in it that points back to the square from which you added it to the worklist. Now, when you are at the exit, you can just follow the arrows back to the start.

Of course, following the arrows gives you the path in reverse order. If only you had a way to keep track of items such that the Last item In was the First item Out, then you could read all the arrows in one pass and write them back out in the correct order...

- Write pseudocode for a method retracePath(Square sq) that prints out the path you found from the start to the Square sq.

Part 4 - Animatronics!

Finally, the last part of the lab will be to add in an animated visual component, so that you can watch your maze solvers do their thing.

Last Modified: September 17, 2015 - Benjamin A. Kuperman - Prelab, GUI, and Minotaurification by Alexa Sharp